import copy

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import warnings

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.preprocessing import MinMaxScaler

from sklearn.gaussian_process import GaussianProcessRegressor

from sklearn.kernel_approximation import Nystroem

from sklearn.gaussian_process.kernels import RBF, WhiteKernel

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from scipy.stats.qmc import LatinHypercube

from scipy.optimize import dual_annealing

from spotdesirability.utils.desirability import DMin, DMax, DOverall

from spotoptim.sampling.mm import mmphi_intensive, mmphi_intensive_update, mm_improvement_contour

from spotoptim.inspection.predictions import plot_actual_vs_predicted

from spotoptim.inspection import (generate_mdi, generate_imp, plot_importances, plot_feature_importances, plot_feature_scatter_matrix)

from spotoptim.utils.boundaries import get_boundaries, map_to_original_scale

from spotoptim.mo.pareto import is_pareto_efficient

from spotoptim.plot.mo import plot_mo

from spotoptim.eda import plot_ip_boxplots, plot_ip_histograms

from spotoptim.utils import get_combinations

from spotoptim.sampling.lhs import rlh

from spotoptim.sampling.mm import (bestlh, plot_mmphi_vs_n_lhs, mmphi, mmphi_intensive, mm_improvement, plot_mmphi_vs_points, mmphi_intensive_update)

from spotoptim.mo import mo_mm_desirability_function, mo_mm_desirability_optimizer

from spotoptim.mo.mo_mm import mo_xy_desirability_plot

from spotoptim.function.mo import mo_conv2_max

from spotoptim.mo.pareto import (mo_xy_surface, mo_xy_contour, mo_pareto_optx_plot)

from spotoptim.utils.eval import mo_cv_models, mo_eval_models

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")24 Multi-Objective Optimization Support in SpotOptim

n_estimators=100

max_depth = None

random_state=4224.1 Overview

SpotOptim supports multi-objective optimization functions with automatic detection and flexible scalarization strategies. The parameter fun_mo2so can be used to convert multi-objective values to single-objective values. If the function fun returns several objective function values, say \(f_1, f_2, \ldots, f_p\), these values are stored in y_mo and can be be used by fun_mo2so. The fun_mo2so parameter is optional. If it is None, which is the default, only the first objective \(f_1\) is used as single-objective and the remaining objectives \(f_2, \ldots, f_p\) are stored in y_mo, but not further used in the optimization process.

fun_mo2so

fun_mo2so(callable, optional): Function to convert multi-objective values to single-objective- Takes array of shape

(n_samples, n_objectives) - Returns array of shape

(n_samples,) - If

None, uses first objective (default behavior)

- Takes array of shape

y_mo(ndarray or None): Stores all multi-objective function values- Shape:

(n_samples, n_objectives)for multi-objective problems Nonefor single-objective problems

- Shape:

get_shape(y): Get shape of objective function outputstore_mo(y_mo): Store multi-objective values with automatic appendingmo2so(y_mo): Convert multi-objective to single-objective values

SpotOptim’s method evaluate_function(X) automatically detects multi-objective functions. It calls mo2so() to convert multi-objective to single-objective. It also stores the original multi-objective values in y_mo. And it returns single-objective values for optimization.

Example 24.2 (Default Behavior (Use First Objective))

Example 24.1

import numpy as np

from spotoptim import SpotOptim

def bi_objective(X):

"""Two conflicting objectives."""

obj1 = np.sum(X**2, axis=1) # Minimize at origin

obj2 = np.sum((X - 2)**2, axis=1) # Minimize at (2, 2)

return np.column_stack([obj1, obj2])

optimizer = SpotOptim(

fun=bi_objective,

bounds=[(-5, 5), (-5, 5)],

max_iter=30,

n_initial=15,

seed=42,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

result = optimizer.optimize()

print(f"Best x: {result.x}") # Near [0, 0]

print(f"Best f(x): {result.fun}") # Minimizes obj1

print(f"MO values stored: {optimizer.y_mo.shape}") # (30, 2)Best x: [4.11141873e-05 2.79358818e-03]

Best f(x): 7.805825304638719e-06

MO values stored: (30, 2)Example 24.4 (Weighted Sum Scalarization)

Example 24.3

def weighted_sum(y_mo):

"""Equal weighting of objectives."""

return 0.5 * y_mo[:, 0] + 0.5 * y_mo[:, 1]

optimizer = SpotOptim(

fun=bi_objective,

bounds=[(-5, 5), (-5, 5)],

max_iter=30,

n_initial=15,

fun_mo2so=weighted_sum, # Custom conversion

seed=42,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

result = optimizer.optimize()

print(f"Compromise solution: {result.x}") # Near [1, 1]Compromise solution: [0.99633399 1.0036975 ]Example 24.6 (Min-Max Scalarization)

Example 24.5

def min_max(y_mo):

"""Minimize the maximum objective."""

return np.max(y_mo, axis=1)

optimizer = SpotOptim(

fun=bi_objective,

bounds=[(-5, 5), (-5, 5)],

max_iter=30,

n_initial=15,

fun_mo2so=min_max,

seed=42,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

result = optimizer.optimize()

# Finds solution with balanced objective valuesExample 24.8 (Three or More Objectives)

Example 24.7

def three_objectives(X):

"""Three different norms."""

obj1 = np.sum(X**2, axis=1) # L2 norm

obj2 = np.sum(np.abs(X), axis=1) # L1 norm

obj3 = np.max(np.abs(X), axis=1) # L-infinity norm

return np.column_stack([obj1, obj2, obj3])

def custom_scalarization(y_mo):

"""Weighted combination."""

return 0.4 * y_mo[:, 0] + 0.3 * y_mo[:, 1] + 0.3 * y_mo[:, 2]

optimizer = SpotOptim(

fun=three_objectives,

bounds=[(-5, 5), (-5, 5), (-5, 5)],

max_iter=35,

n_initial=20,

fun_mo2so=custom_scalarization,

seed=42,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

result = optimizer.optimize()Example 24.10 (Noise Handling)

Example 24.9

def noisy_bi_objective(X):

"""Noisy multi-objective function."""

noise1 = np.random.normal(0, 0.05, X.shape[0])

noise2 = np.random.normal(0, 0.05, X.shape[0])

obj1 = np.sum(X**2, axis=1) + noise1

obj2 = np.sum((X - 1)**2, axis=1) + noise2

return np.column_stack([obj1, obj2])

optimizer = SpotOptim(

fun=noisy_bi_objective,

bounds=[(-5, 5), (-5, 5)],

max_iter=40,

n_initial=10,

repeats_initial=3, # Handle noise

repeats_surrogate=2,

seed=42,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

result = optimizer.optimize()

# Works seamlessly with noise handling24.2 Common Scalarization Strategies

24.2.1 1. Weighted Sum

def weighted_sum(y_mo, weights=[0.5, 0.5]):

return sum(w * y_mo[:, i] for i, w in enumerate(weights))Use when: Objectives have similar scales and you want linear trade-offs

24.2.2 2. Weighted Sum with Normalization

def normalized_weighted_sum(y_mo, weights=[0.5, 0.5]):

# Normalize each objective to [0, 1]

y_norm = (y_mo - y_mo.min(axis=0)) / (y_mo.max(axis=0) - y_mo.min(axis=0) + 1e-10)

return sum(w * y_norm[:, i] for i, w in enumerate(weights))Use when: Objectives have very different scales

24.2.3 3. Min-Max (Chebyshev)

def min_max(y_mo):

return np.max(y_mo, axis=1)Use when: You want balanced performance across all objectives

24.2.4 4. Target Achievement

def target_achievement(y_mo, targets=[0.0, 0.0]):

# Minimize deviation from targets

return np.sum((y_mo - targets)**2, axis=1)Use when: You have specific target values for each objective

24.2.5 5. Product

def product(y_mo):

return np.prod(y_mo + 1e-10, axis=1) # Add small value to avoid zeroUse when: All objectives should be minimized together

24.3 Integration with Other Features

Multi-objective support works seamlessly with:

✅ Noise Handling - Use repeats_initial and repeats_surrogate

✅ OCBA - Use ocba_delta for intelligent re-evaluation

✅ TensorBoard Logging - Logs converted single-objective values

✅ Dimension Reduction - Fixed dimensions work normally

✅ Custom Variable Names - var_name parameter supported

24.4 Implementation Details

24.4.1 Automatic Detection

SpotOptim automatically detects multi-objective functions:

- If function returns 2D array (n_samples, n_objectives), it’s multi-objective

- If function returns 1D array (n_samples,), it’s single-objective

24.4.2 Data Flow

User Function → y_mo (raw) → mo2so() → y_ (single-objective)

↓

y_mo (stored)- Function returns multi-objective values

store_mo()saves them iny_moattributemo2so()converts to single-objective usingfun_mo2soor default- Surrogate model optimizes the single-objective values

- All original multi-objective values remain accessible in

y_mo

24.4.3 Backward Compatibility

✅ Fully backward compatible:

- Single-objective functions work unchanged

fun_mo2sodefaults toNoney_moisNonefor single-objective problems- No breaking changes to existing code

24.5 Limitations and Notes

24.5.1 What This Is

- ✅ Scalarization approach to multi-objective optimization

- ✅ Single solution found per optimization run

- ✅ Different scalarizations → different Pareto solutions

- ✅ Suitable for preference-based multi-objective optimization

24.5.2 What This Is Not

- ❌ Not a true multi-objective optimizer (doesn’t find Pareto front)

- ❌ Doesn’t generate multiple solutions in one run

- ❌ Not suitable for discovering entire Pareto front

24.5.3 For True Multi-Objective Optimization

For finding the complete Pareto front, consider specialized tools:

- pymoo: Comprehensive multi-objective optimization framework

- platypus: Multi-objective optimization library

- NSGA-II, MOEA/D: Dedicated multi-objective algorithms

24.6 Benchmark Multi-Objective Test Functions

SpotOptim includes 12 multi-objective benchmark functions in spotoptim.function.mo. These functions are widely used to evaluate and compare multi-objective optimization algorithms.

24.6.1 Function Overview

| Function | Objectives | Variables | Pareto Front | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZDT1 | 2 | 30 | Convex | Unimodal, minimization |

| ZDT2 | 2 | 30 | Non-convex | Unimodal, minimization |

| ZDT3 | 2 | 30 | Disconnected | Multimodal, minimization |

| ZDT4 | 2 | 10 | Convex | Many local fronts |

| ZDT6 | 2 | 10 | Non-convex | Non-uniform density |

| DTLZ1 | Scalable | n_obj+4 | Linear | Multimodal |

| DTLZ2 | Scalable | n_obj+9 | Spherical | Unimodal |

| Schaffer N1 | 2 | 1 | Convex | Simple, minimization |

| Fonseca-Fleming | 2 | 2-10 | Concave | Symmetric, minimization |

| mo_conv2_min | 2 | 2 | Convex | Convex, minimization |

| mo_conv2_max | 2 | 2 | Convex | Convex, maximization |

| Kursawe | 2 | 3 | Disconnected | Non-convex, disconnected minimization |

mo_conv2_min is a smooth convex minimization pair with objectives \(f_1(x, y) = x^2 + y^2\) and \(f_2(x, y) = (x - 1)^2 + (y - 1)^2\) on \([0, 1]^2\), producing a convex quadratic Pareto front along \(x = y\). mo_conv2_max flips both objectives for maximization via \(f_1(x, y) = 2 - (x^2 + y^2)\) and \(f_2(x, y) = 2 - ((1 - x)^2 + (1 - y)^2)\), keeping objective values bounded in \([0, 2]\).

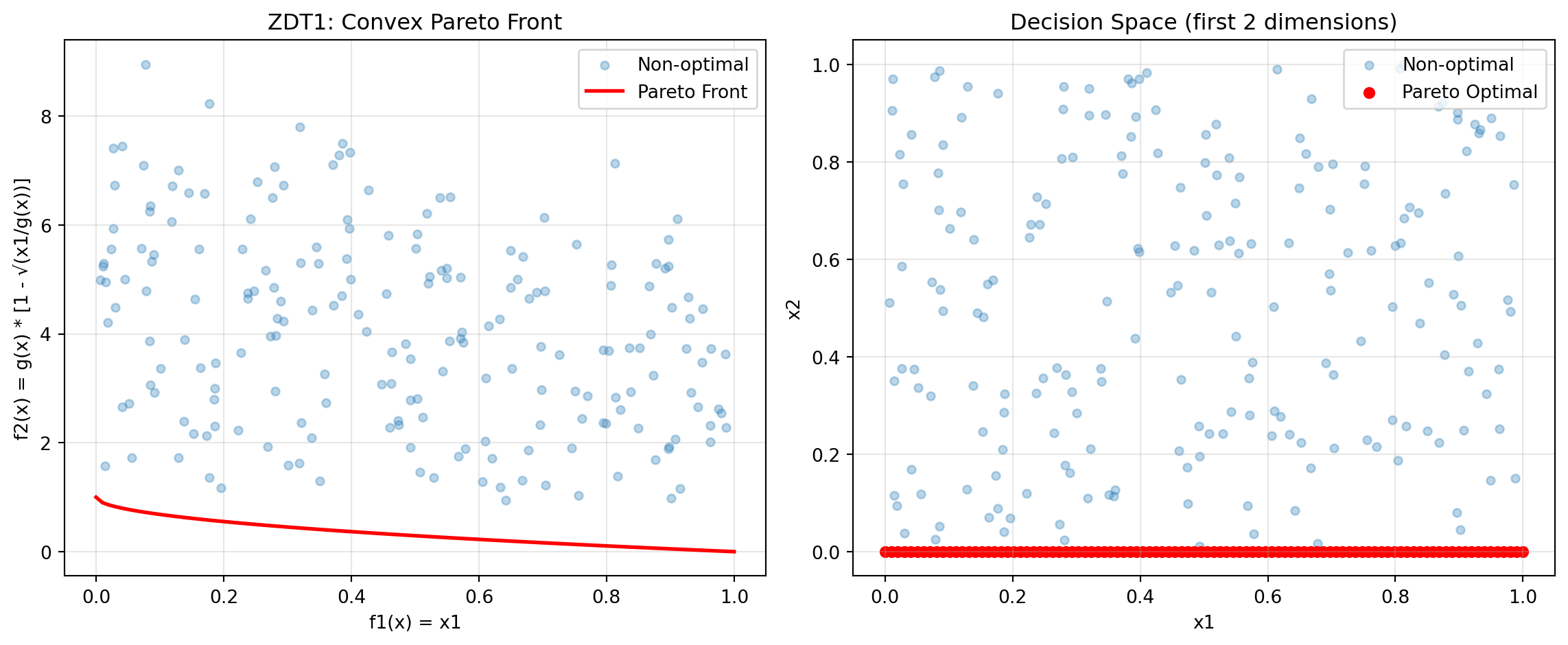

24.6.2 Example 6: ZDT1 - Convex Pareto Front

ZDT1 is a classical bi-objective test problem with a convex Pareto front, widely used for benchmarking.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from spotoptim.function.mo import zdt1

from spotoptim import SpotOptim

# Generate data for visualization

n_points = 100

x1_range = np.linspace(0, 1, n_points)

# Pareto front: x1 in [0,1], rest = 0

X_pareto = np.column_stack([x1_range, np.zeros((n_points, 2))])

y_pareto = zdt1(X_pareto)

# Non-optimal points for comparison

X_non_optimal = np.random.rand(200, 3)

y_non_optimal = zdt1(X_non_optimal)Figure 24.1 visualizes the Pareto front:

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Plot objective space

ax1.scatter(y_non_optimal[:, 0], y_non_optimal[:, 1],

alpha=0.3, label='Non-optimal', s=20)

ax1.plot(y_pareto[:, 0], y_pareto[:, 1],

'r-', linewidth=2, label='Pareto Front')

ax1.set_xlabel('f1(x) = x1')

ax1.set_ylabel('f2(x) = g(x) * [1 - √(x1/g(x))]')

ax1.set_title('ZDT1: Convex Pareto Front')

ax1.legend()

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Plot decision space (first two variables)

ax2.scatter(X_non_optimal[:, 0], X_non_optimal[:, 1],

alpha=0.3, label='Non-optimal', s=20)

ax2.scatter(X_pareto[:, 0], X_pareto[:, 1],

c='red', label='Pareto Optimal', s=30)

ax2.set_xlabel('x1')

ax2.set_ylabel('x2')

ax2.set_title('Decision Space (first 2 dimensions)')

ax2.legend()

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("ZDT1 Characteristics:")

print("- Convex Pareto front: f2 = 1 - √f1")

print("- Optimal when x2, x3, ..., xn = 0")

print("- Easy to solve, good for testing basic functionality")ZDT1 Characteristics:

- Convex Pareto front: f2 = 1 - √f1

- Optimal when x2, x3, ..., xn = 0

- Easy to solve, good for testing basic functionalityNow optimize using SpotOptim with weighted sum:

def weighted_sum_zdt1(y_mo):

"""Equal weighting for ZDT1."""

return 0.5 * y_mo[:, 0] + 0.5 * y_mo[:, 1]

optimizer = SpotOptim(

fun=zdt1,

bounds=[(0, 1)] * 30, # 30 variables in [0, 1]

max_iter=50,

n_initial=20,

fun_mo2so=weighted_sum_zdt1,

seed=42,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

result = optimizer.optimize()

print(f"\nOptimization Result:")

print(f"Best x (first 5 dims): {result.x[:5]}")

print(f"Best scalarized value: {result.fun:.6f}")

# Evaluate multi-objective values

y_best = zdt1(result.x.reshape(1, -1))

print(f"f1 = {y_best[0, 0]:.6f}, f2 = {y_best[0, 1]:.6f}")

Optimization Result:

Best x (first 5 dims): [1. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

Best scalarized value: 0.500000

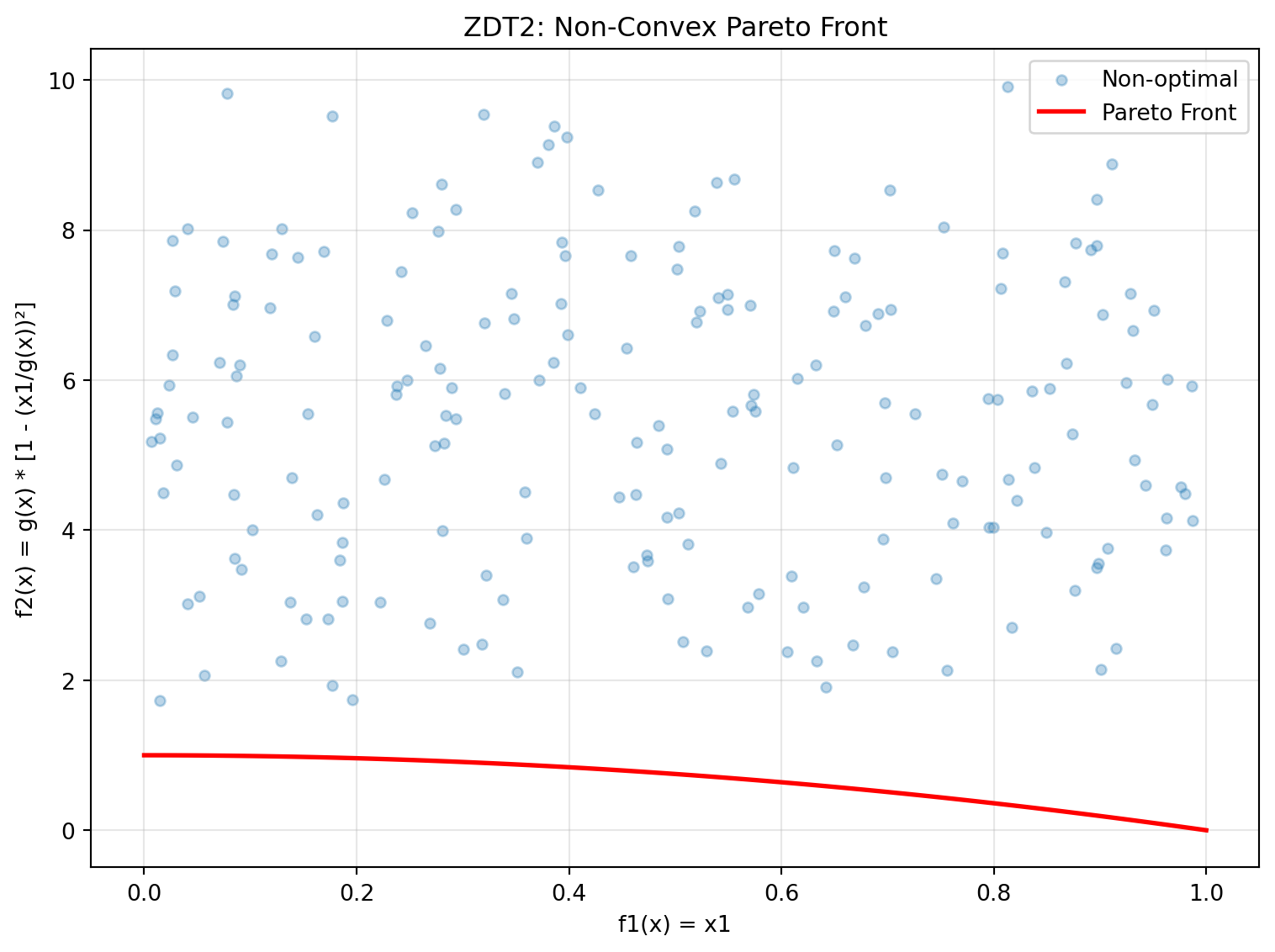

f1 = 1.000000, f2 = 0.00000024.6.3 Example 7: ZDT2 - Non-Convex Pareto Front

ZDT2 has a non-convex Pareto front, making it more challenging than ZDT1.

from spotoptim.function.mo import zdt2

# Generate Pareto front

X_pareto = np.column_stack([x1_range, np.zeros((n_points, 2))])

y_pareto = zdt2(X_pareto)

# Non-optimal points

y_non_optimal = zdt2(X_non_optimal)Figure 24.2 visualizes the Pareto front:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 6))

ax.scatter(y_non_optimal[:, 0], y_non_optimal[:, 1],

alpha=0.3, label='Non-optimal', s=20)

ax.plot(y_pareto[:, 0], y_pareto[:, 1],

'r-', linewidth=2, label='Pareto Front')

ax.set_xlabel('f1(x) = x1')

ax.set_ylabel('f2(x) = g(x) * [1 - (x1/g(x))²]')

ax.set_title('ZDT2: Non-Convex Pareto Front')

ax.legend()

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("ZDT2 Characteristics:")

print("- Non-convex Pareto front: f2 = 1 - f1²")

print("- Tests algorithm's ability to handle non-convexity")

print("- Optimal when x2, x3, ..., xn = 0")ZDT2 Characteristics:

- Non-convex Pareto front: f2 = 1 - f1²

- Tests algorithm's ability to handle non-convexity

- Optimal when x2, x3, ..., xn = 024.6.4 Example 8: ZDT3 - Disconnected Pareto Front

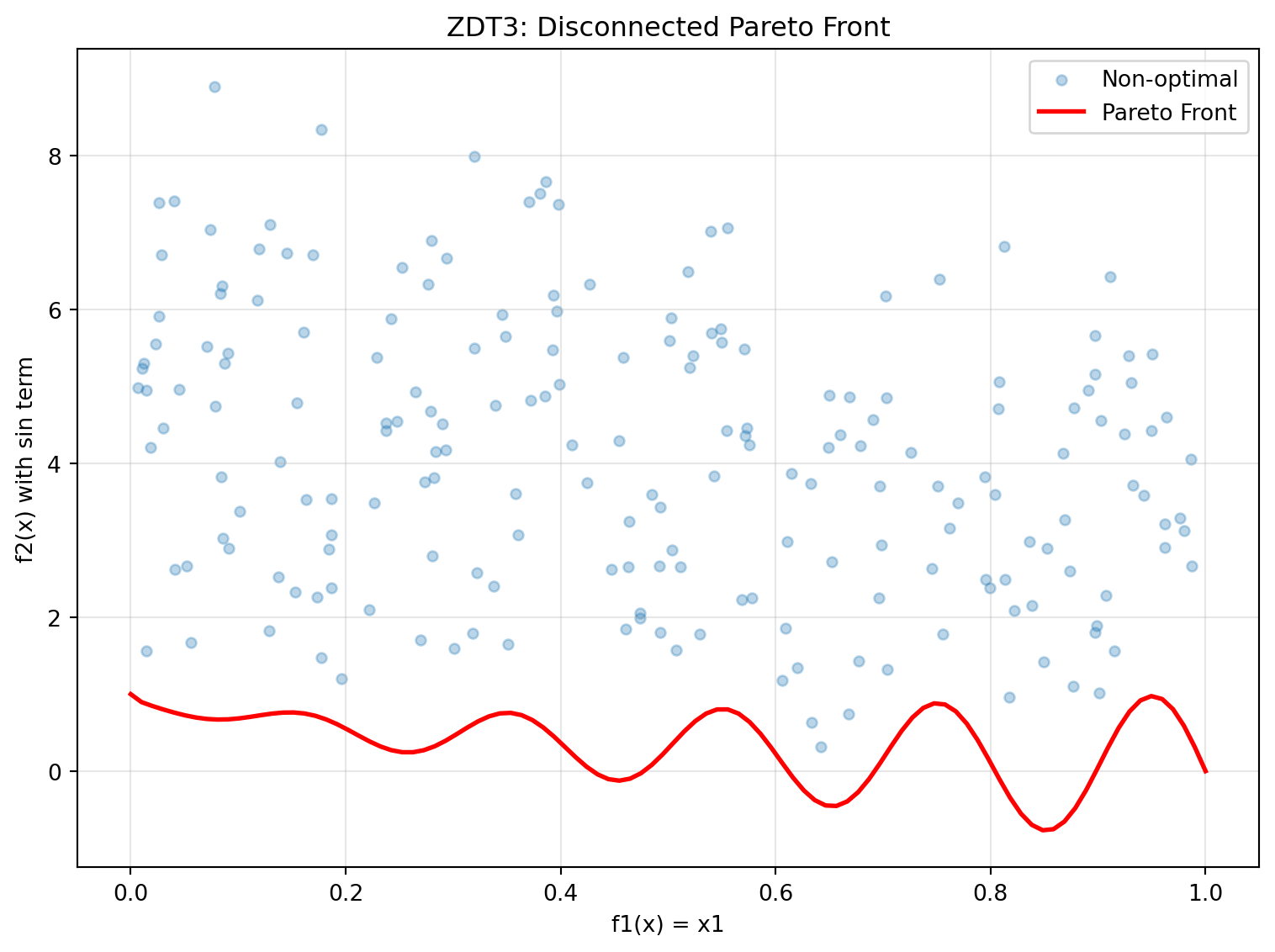

ZDT3 has a discontinuous Pareto front consisting of 5 separate regions.

from spotoptim.function.mo import zdt3

# Generate Pareto front

X_pareto = np.column_stack([x1_range, np.zeros((n_points, 2))])

y_pareto = zdt3(X_pareto)

# Non-optimal points

y_non_optimal = zdt3(X_non_optimal)Figure 24.3 visualizes the Pareto front:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 6))

ax.scatter(y_non_optimal[:, 0], y_non_optimal[:, 1],

alpha=0.3, label='Non-optimal', s=20)

ax.plot(y_pareto[:, 0], y_pareto[:, 1],

'r-', linewidth=2, label='Pareto Front')

ax.set_xlabel('f1(x) = x1')

ax.set_ylabel('f2(x) with sin term')

ax.set_title('ZDT3: Disconnected Pareto Front')

ax.legend()

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("ZDT3 Characteristics:")

print("- Disconnected Pareto front with 5 separate regions")

print("- Tests diversity maintenance in algorithms")

print("- sin(10πx1) term creates discontinuities")ZDT3 Characteristics:

- Disconnected Pareto front with 5 separate regions

- Tests diversity maintenance in algorithms

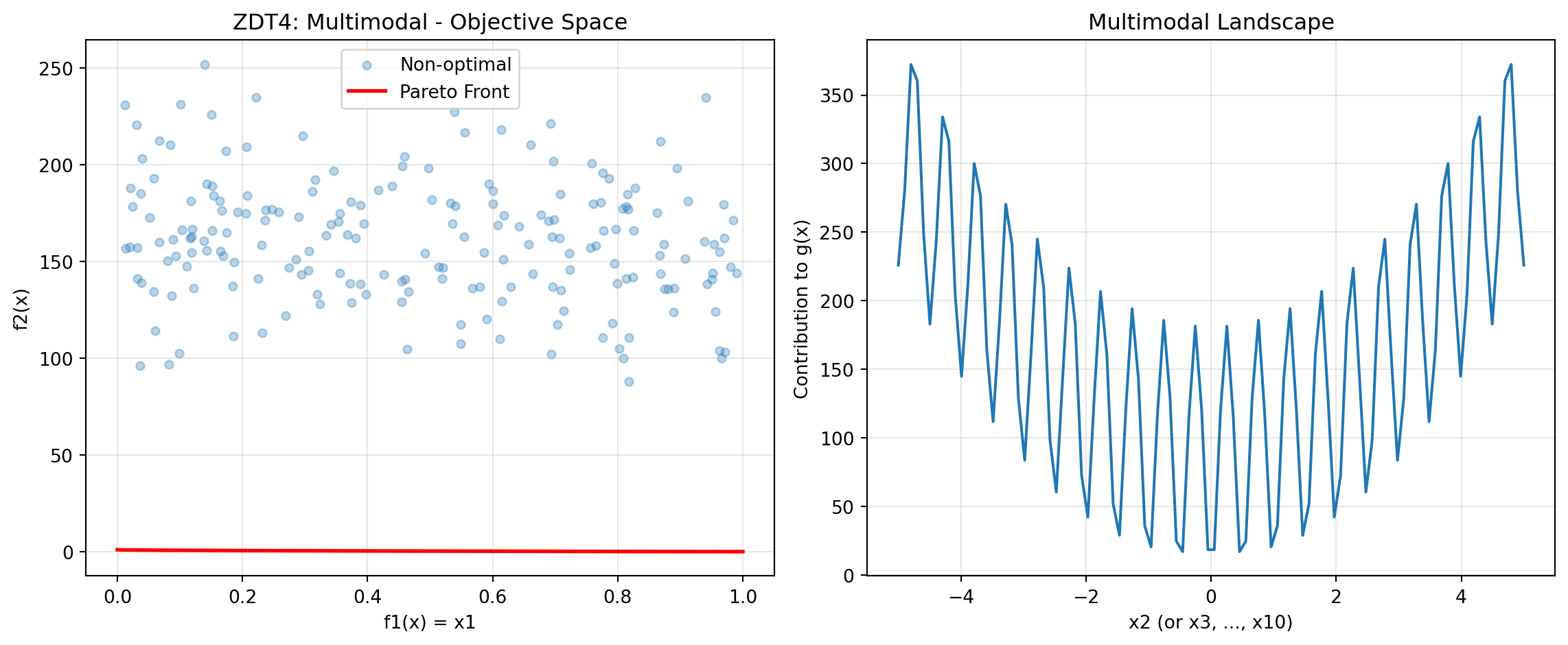

- sin(10πx1) term creates discontinuities24.6.5 Example 9: ZDT4 - Multimodal with Many Local Fronts

ZDT4 has 21^9 local Pareto fronts, testing the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima.

from spotoptim.function.mo import zdt4

# Generate Pareto front (same as ZDT1 when optimal)

X_pareto = np.column_stack([x1_range, np.zeros((n_points, 9))])

y_pareto = zdt4(X_pareto)

# Non-optimal points with multimodal g-function

X_non_optimal_zdt4 = np.random.rand(200, 10)

X_non_optimal_zdt4[:, 0] = np.clip(X_non_optimal_zdt4[:, 0], 0, 1) # x1 in [0,1]

X_non_optimal_zdt4[:, 1:] = X_non_optimal_zdt4[:, 1:] * 10 - 5 # others in [-5,5]

y_non_optimal = zdt4(X_non_optimal_zdt4)Figure 24.4 visualizes the Pareto front:

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Objective space

ax1.scatter(y_non_optimal[:, 0], y_non_optimal[:, 1],

alpha=0.3, label='Non-optimal', s=20)

ax1.plot(y_pareto[:, 0], y_pareto[:, 1],

'r-', linewidth=2, label='Pareto Front')

ax1.set_xlabel('f1(x) = x1')

ax1.set_ylabel('f2(x)')

ax1.set_title('ZDT4: Multimodal - Objective Space')

ax1.legend()

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Show multimodal landscape for x2

x2_range = np.linspace(-5, 5, 100)

g_vals = 1 + 10 * 9 + (x2_range**2 - 10 * np.cos(4 * np.pi * x2_range)) * 9

ax2.plot(x2_range, g_vals)

ax2.set_xlabel('x2 (or x3, ..., x10)')

ax2.set_ylabel('Contribution to g(x)')

ax2.set_title('Multimodal Landscape')

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("ZDT4 Characteristics:")

print("- 21^9 local Pareto fronts")

print("- Tests global search capability")

print("- x1 in [0,1], x_i in [-5,5] for i=2,...,10")ZDT4 Characteristics:

- 21^9 local Pareto fronts

- Tests global search capability

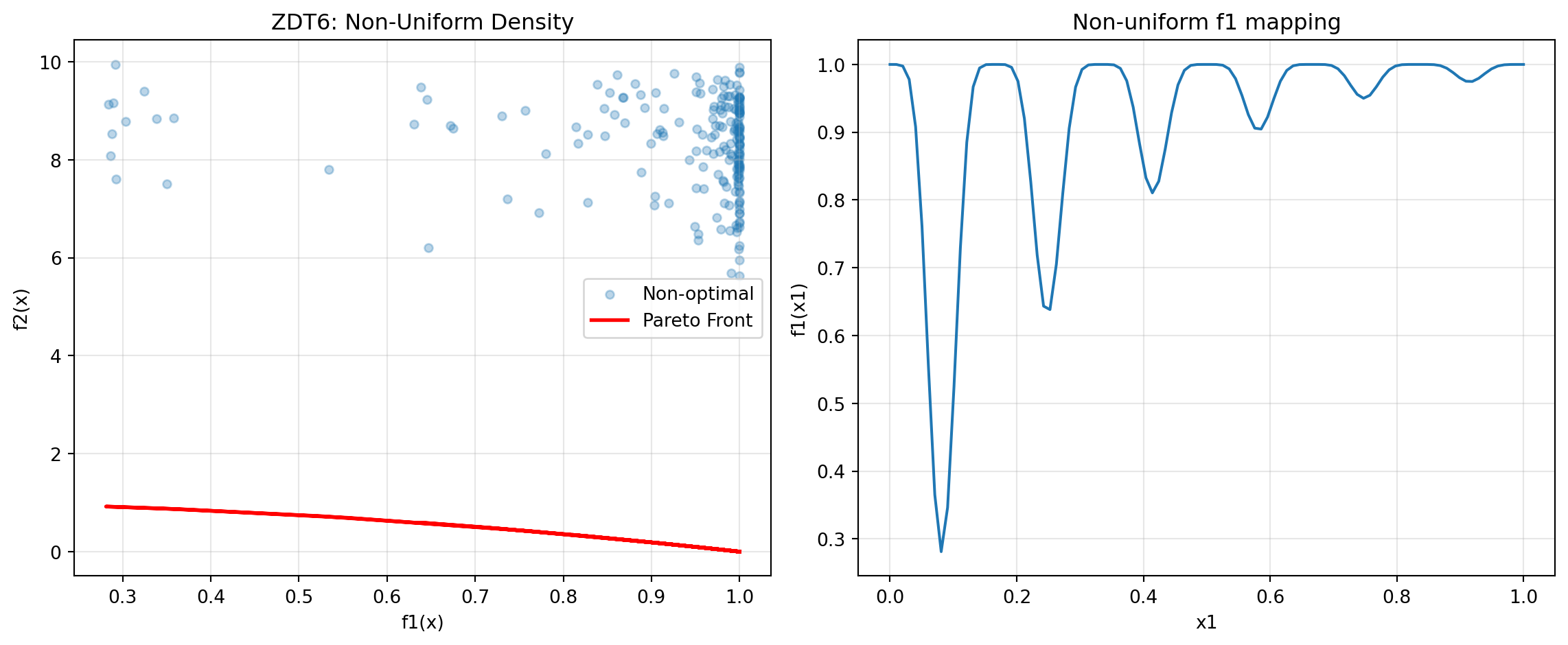

- x1 in [0,1], x_i in [-5,5] for i=2,...,1024.6.6 Example 10: ZDT6 - Non-Uniform Density

ZDT6 has a non-uniform search space with low density of solutions near the Pareto front.

from spotoptim.function.mo import zdt6

# Generate Pareto front

X_pareto = np.column_stack([x1_range, np.zeros((n_points, 2))])

y_pareto = zdt6(X_pareto)

# Non-optimal points

y_non_optimal = zdt6(X_non_optimal)Figure 24.5 visualizes the Pareto front:

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Objective space

ax1.scatter(y_non_optimal[:, 0], y_non_optimal[:, 1],

alpha=0.3, label='Non-optimal', s=20)

ax1.plot(y_pareto[:, 0], y_pareto[:, 1],

'r-', linewidth=2, label='Pareto Front')

ax1.set_xlabel('f1(x)')

ax1.set_ylabel('f2(x)')

ax1.set_title('ZDT6: Non-Uniform Density')

ax1.legend()

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Show f1 non-uniformity

ax2.plot(x1_range, 1 - np.exp(-4 * x1_range) * (np.sin(6 * np.pi * x1_range)**6))

ax2.set_xlabel('x1')

ax2.set_ylabel('f1(x1)')

ax2.set_title('Non-uniform f1 mapping')

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("ZDT6 Characteristics:")

print("- Non-uniform density of Pareto optimal solutions")

print("- Low density near the Pareto front")

print("- Tests diversity maintenance")ZDT6 Characteristics:

- Non-uniform density of Pareto optimal solutions

- Low density near the Pareto front

- Tests diversity maintenance24.6.7 Example 11: DTLZ2 - Scalable Spherical Pareto Front

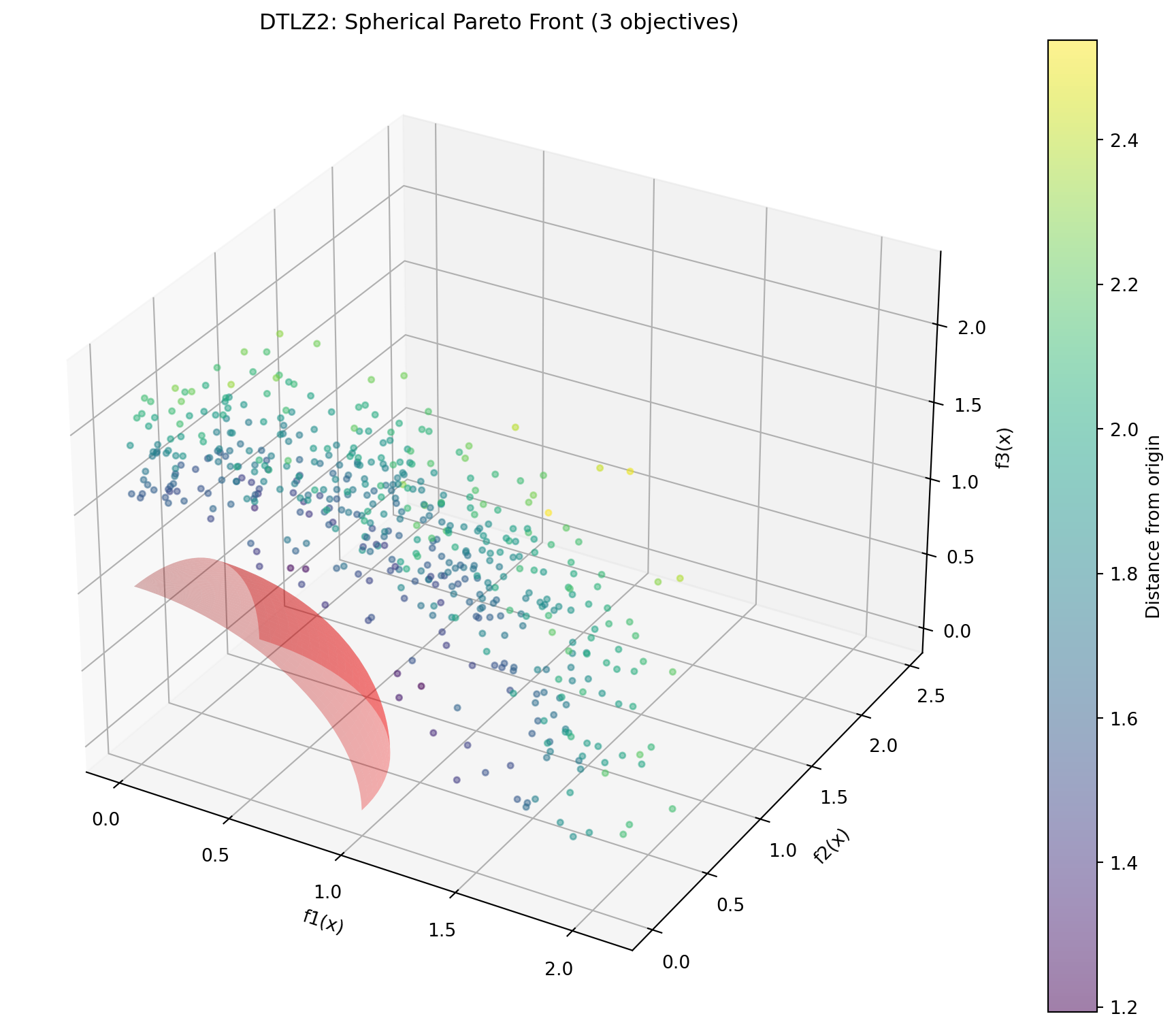

DTLZ2 is a scalable test problem with a concave spherical Pareto front.

from spotoptim.function.mo import dtlz2

# 3D visualization for 3 objectives

n_samples = 500

X_samples = np.random.rand(n_samples, 12)

y_samples = dtlz2(X_samples, n_obj=3)

# Generate Pareto optimal points (on unit sphere)

theta = np.linspace(0, np.pi/2, 30)

phi = np.linspace(0, np.pi/2, 30)

theta_grid, phi_grid = np.meshgrid(theta, phi)

f1 = np.cos(theta_grid) * np.cos(phi_grid)

f2 = np.cos(theta_grid) * np.sin(phi_grid)

f3 = np.sin(theta_grid)Figure 24.6 visualizes the Pareto front:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# Pareto front surface

ax.plot_surface(f1, f2, f3, alpha=0.3, color='red', label='Pareto Front')

# Sample points

colors = np.linalg.norm(y_samples, axis=1)

scatter = ax.scatter(y_samples[:, 0], y_samples[:, 1], y_samples[:, 2],

c=colors, cmap='viridis', alpha=0.5, s=10)

ax.set_xlabel('f1(x)')

ax.set_ylabel('f2(x)')

ax.set_zlabel('f3(x)')

ax.set_title('DTLZ2: Spherical Pareto Front (3 objectives)')

plt.colorbar(scatter, label='Distance from origin')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("DTLZ2 Characteristics:")

print("- Scalable number of objectives")

print("- Pareto front is unit sphere: Σf_i² = 1")

print("- Concave, unimodal")

print(f"- Sample: sum of squares = {np.sum(y_samples[0]**2):.4f}")DTLZ2 Characteristics:

- Scalable number of objectives

- Pareto front is unit sphere: Σf_i² = 1

- Concave, unimodal

- Sample: sum of squares = 4.0966Optimize DTLZ2 with 3 objectives:

def weighted_sum_3obj(y_mo):

"""Equal weighting for 3 objectives."""

return np.mean(y_mo, axis=1)

optimizer = SpotOptim(

fun=lambda X: dtlz2(X, n_obj=3),

bounds=[(0, 1)] * 12, # 12 variables for 3 objectives

max_iter=50,

n_initial=25,

fun_mo2so=weighted_sum_3obj,

seed=42,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

result = optimizer.optimize()

# Evaluate

y_best = dtlz2(result.x.reshape(1, -1), n_obj=3)

print(f"\nOptimization Result:")

print(f"f1 = {y_best[0, 0]:.4f}, f2 = {y_best[0, 1]:.4f}, f3 = {y_best[0, 2]:.4f}")

print(f"Sum of squares: {np.sum(y_best[0]**2):.4f} (should be ~1.0)")

Optimization Result:

f1 = 0.0000, f2 = 0.0000, f3 = 1.3558

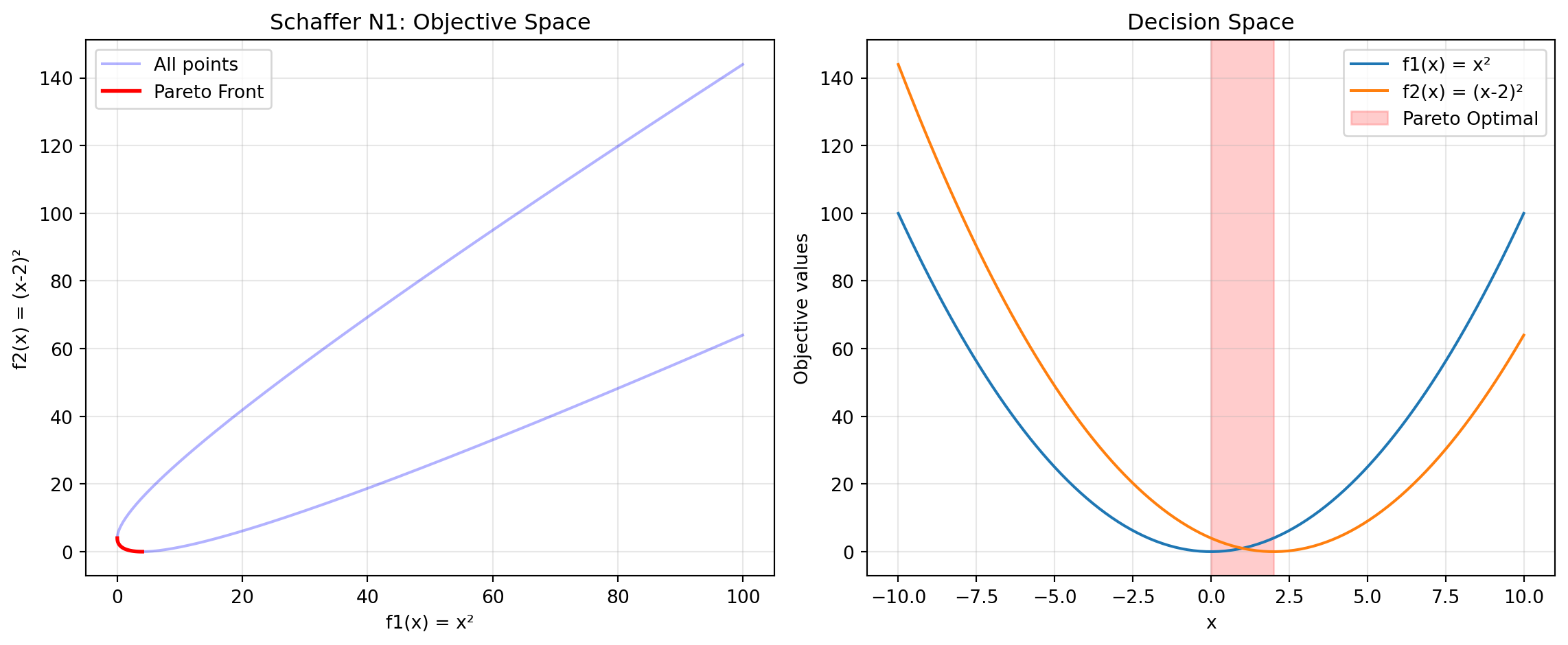

Sum of squares: 1.8382 (should be ~1.0)24.6.8 Example 12: Schaffer N1 - Simple Bi-Objective

Schaffer N1 is one of the earliest and simplest multi-objective test functions.

from spotoptim.function.mo import schaffer_n1

# Generate data

x_range = np.linspace(-10, 10, 200).reshape(-1, 1)

y_schaffer = schaffer_n1(x_range)

# Pareto optimal range [0, 2]

x_pareto = np.linspace(0, 2, 100).reshape(-1, 1)

y_pareto = schaffer_n1(x_pareto)Figure 24.7 visualizes the Pareto front:

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Objective space

ax1.plot(y_schaffer[:, 0], y_schaffer[:, 1], 'b-', alpha=0.3, label='All points')

ax1.plot(y_pareto[:, 0], y_pareto[:, 1], 'r-', linewidth=2, label='Pareto Front')

ax1.set_xlabel('f1(x) = x²')

ax1.set_ylabel('f2(x) = (x-2)²')

ax1.set_title('Schaffer N1: Objective Space')

ax1.legend()

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Decision space

ax2.plot(x_range, y_schaffer[:, 0], label='f1(x) = x²')

ax2.plot(x_range, y_schaffer[:, 1], label='f2(x) = (x-2)²')

ax2.axvspan(0, 2, alpha=0.2, color='red', label='Pareto Optimal')

ax2.set_xlabel('x')

ax2.set_ylabel('Objective values')

ax2.set_title('Decision Space')

ax2.legend()

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("Schaffer N1 Characteristics:")

print("- Simplest multi-objective function")

print("- 1D decision variable")

print("- Pareto optimal: x ∈ [0, 2]")

print("- Convex Pareto front")Schaffer N1 Characteristics:

- Simplest multi-objective function

- 1D decision variable

- Pareto optimal: x ∈ [0, 2]

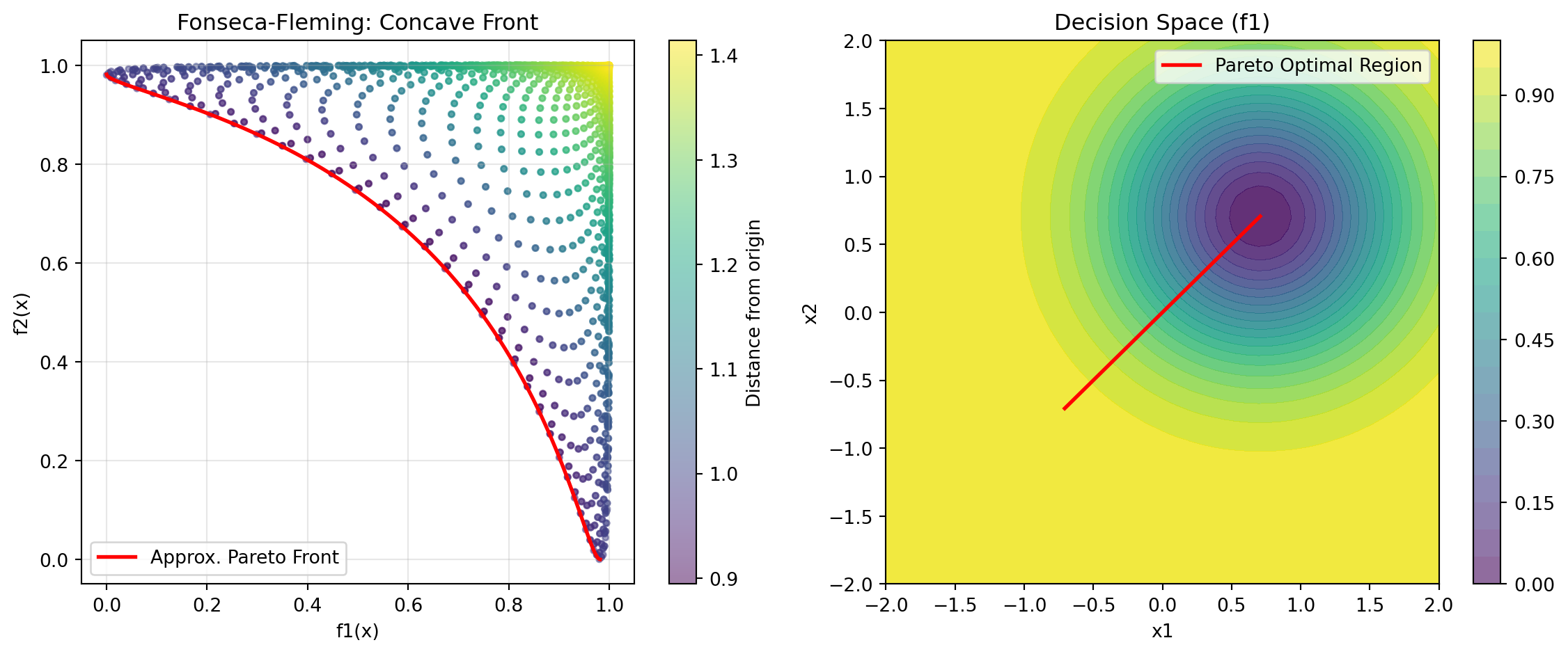

- Convex Pareto front24.6.9 Example 13: Fonseca-Fleming - Symmetric Concave Front

Fonseca-Fleming is a classical bi-objective problem with a concave Pareto front. It is defined for 2 to 10 decision variables as follows: \[ f_1(x) = 1 - \exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}})^2\right) f_2(x) = 1 - \exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i + \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}})^2\right), \] where \(x_i \in [-2, 2]\). The Pareto optimal solutions satisfy: \[ \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i^2 = \frac{1}{n}. \]

from spotoptim.function.mo import fonseca_fleming

# Generate data for 2D

n_grid = 50

x1_ff = np.linspace(-2, 2, n_grid)

x2_ff = np.linspace(-2, 2, n_grid)

X1_grid, X2_grid = np.meshgrid(x1_ff, x2_ff)

# Evaluate on grid

X_grid = np.column_stack([X1_grid.ravel(), X2_grid.ravel()])

y_grid = fonseca_fleming(X_grid)

# Pareto optimal points (approximately)

X_pareto_ff = np.linspace(-1/np.sqrt(2), 1/np.sqrt(2), 100)

X_pareto_2d = np.column_stack([X_pareto_ff, X_pareto_ff])

y_pareto_ff = fonseca_fleming(X_pareto_2d)Figure 24.8 visualizes the Pareto front:

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Objective space

scatter = ax1.scatter(y_grid[:, 0], y_grid[:, 1],

c=np.linalg.norm(y_grid, axis=1),

cmap='viridis', alpha=0.5, s=10)

ax1.plot(y_pareto_ff[:, 0], y_pareto_ff[:, 1],

'r-', linewidth=2, label='Approx. Pareto Front')

ax1.set_xlabel('f1(x)')

ax1.set_ylabel('f2(x)')

ax1.set_title('Fonseca-Fleming: Concave Front')

ax1.legend()

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.colorbar(scatter, ax=ax1, label='Distance from origin')

# Decision space

ax2.contourf(X1_grid, X2_grid, y_grid[:, 0].reshape(n_grid, n_grid),

levels=20, cmap='viridis', alpha=0.6)

ax2.plot(X_pareto_2d[:, 0], X_pareto_2d[:, 1],

'r-', linewidth=2, label='Pareto Optimal Region')

ax2.set_xlabel('x1')

ax2.set_ylabel('x2')

ax2.set_title('Decision Space (f1)')

ax2.legend()

plt.colorbar(ax2.contourf(X1_grid, X2_grid, y_grid[:, 0].reshape(n_grid, n_grid),

levels=20, cmap='viridis', alpha=0.6), ax=ax2)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("Fonseca-Fleming Characteristics:")

print("- Concave Pareto front (minimization)")

print("- Symmetric problem")

print("- Scalable to higher dimensions")Fonseca-Fleming Characteristics:

- Concave Pareto front (minimization)

- Symmetric problem

- Scalable to higher dimensions24.7 Example 14: Kursawe - Non-Convex Disconnected Front

Optimize Kursawe with min-max scalarization:

from spotoptim.function.mo import kursawe

def min_max_kursawe(y_mo):

"""Minimize maximum objective (Chebyshev)."""

return np.max(y_mo, axis=1)

optimizer = SpotOptim(

fun=kursawe,

bounds=[(-5, 5)] * 3,

max_iter=50,

n_initial=20,

fun_mo2so=min_max_kursawe,

seed=42,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

result = optimizer.optimize()

y_best = kursawe(result.x.reshape(1, -1))

print(f"\nOptimization Result:")

print(f"Best x: {result.x}")

print(f"f1 = {y_best[0, 0]:.4f}, f2 = {y_best[0, 1]:.4f}")

print(f"Max objective: {max(y_best[0]):.4f}")

Optimization Result:

Best x: [-1.14002298 -1.07146623 -1.12693436]

f1 = -14.6404, f2 = -11.3764

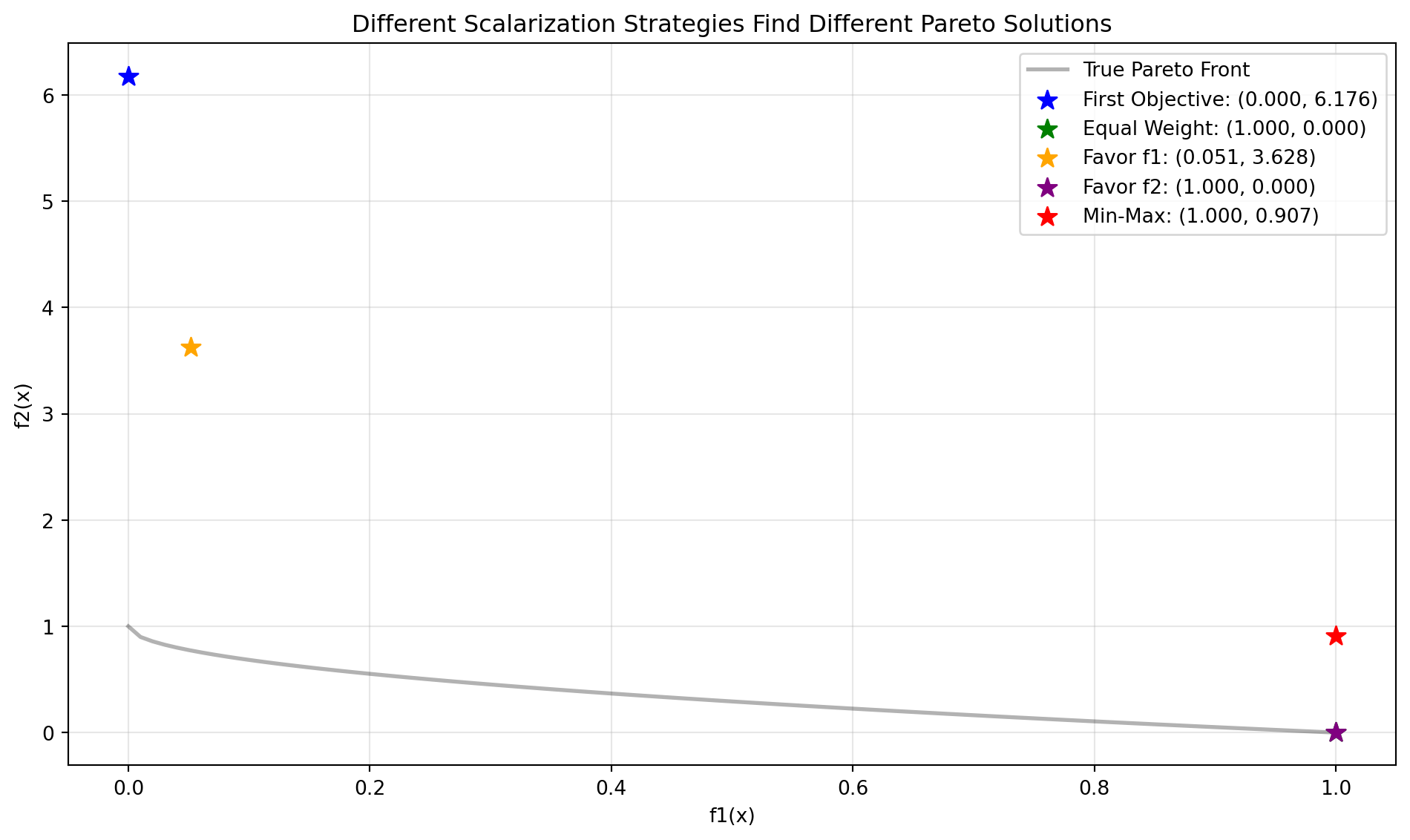

Max objective: -11.376424.7.1 Comparison: Different Scalarization Strategies on ZDT1

Let’s compare how different scalarization strategies find different Pareto solutions:

scalarizations = {

'First Objective': None, # Default

'Equal Weight': lambda y: 0.5 * y[:, 0] + 0.5 * y[:, 1],

'Favor f1': lambda y: 0.8 * y[:, 0] + 0.2 * y[:, 1],

'Favor f2': lambda y: 0.2 * y[:, 0] + 0.8 * y[:, 1],

'Min-Max': lambda y: np.max(y, axis=1),

}

results = {}

for name, scalarization in scalarizations.items():

opt = SpotOptim(

fun=zdt1,

bounds=[(0, 1)] * 30,

max_iter=40,

n_initial=15,

fun_mo2so=scalarization,

seed=42,

verbose=0,

max_surrogate_points=30

)

res = opt.optimize()

y_res = zdt1(res.x.reshape(1, -1))

results[name] = (res.x, y_res[0])Figure 24.9 visualizes the results:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

# Plot Pareto front

X_pareto = np.column_stack([x1_range, np.zeros((n_points, 29))])

y_pareto = zdt1(X_pareto)

ax.plot(y_pareto[:, 0], y_pareto[:, 1], 'k-', linewidth=2,

label='True Pareto Front', alpha=0.3)

# Plot optimization results

colors = ['blue', 'green', 'orange', 'purple', 'red']

for (name, (x, y)), color in zip(results.items(), colors):

ax.scatter(y[0], y[1], s=100, c=color, marker='*',

label=f'{name}: ({y[0]:.3f}, {y[1]:.3f})', zorder=5)

ax.set_xlabel('f1(x)')

ax.set_ylabel('f2(x)')

ax.set_title('Different Scalarization Strategies Find Different Pareto Solutions')

ax.legend()

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("\nComparison Results:")

for name, (x, y) in results.items():

print(f"{name:20s}: f1={y[0]:.4f}, f2={y[1]:.4f}")

Comparison Results:

First Objective : f1=0.0000, f2=6.1756

Equal Weight : f1=1.0000, f2=0.0000

Favor f1 : f1=0.0540, f2=3.7292

Favor f2 : f1=1.0000, f2=0.0000

Min-Max : f1=0.9996, f2=0.697024.8 A Simple Visualization Example

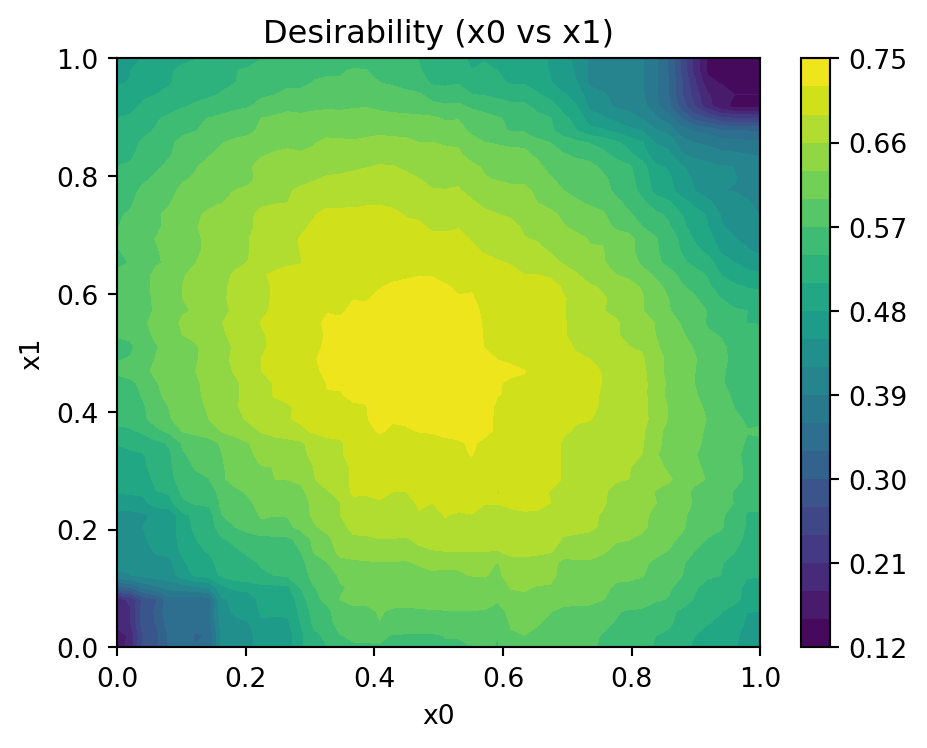

The mo_mm_desirability_function computes the negative combined desirability for a candidate point x. It predicts the objective values using the provided surrogate models, computes the Morris-Mitchell improvement if requested, and then calculates the overall desirability using the provided DOverall object. The function returns the negative desirability (for minimization) and the list of individual objective values. Consider the following example usage:

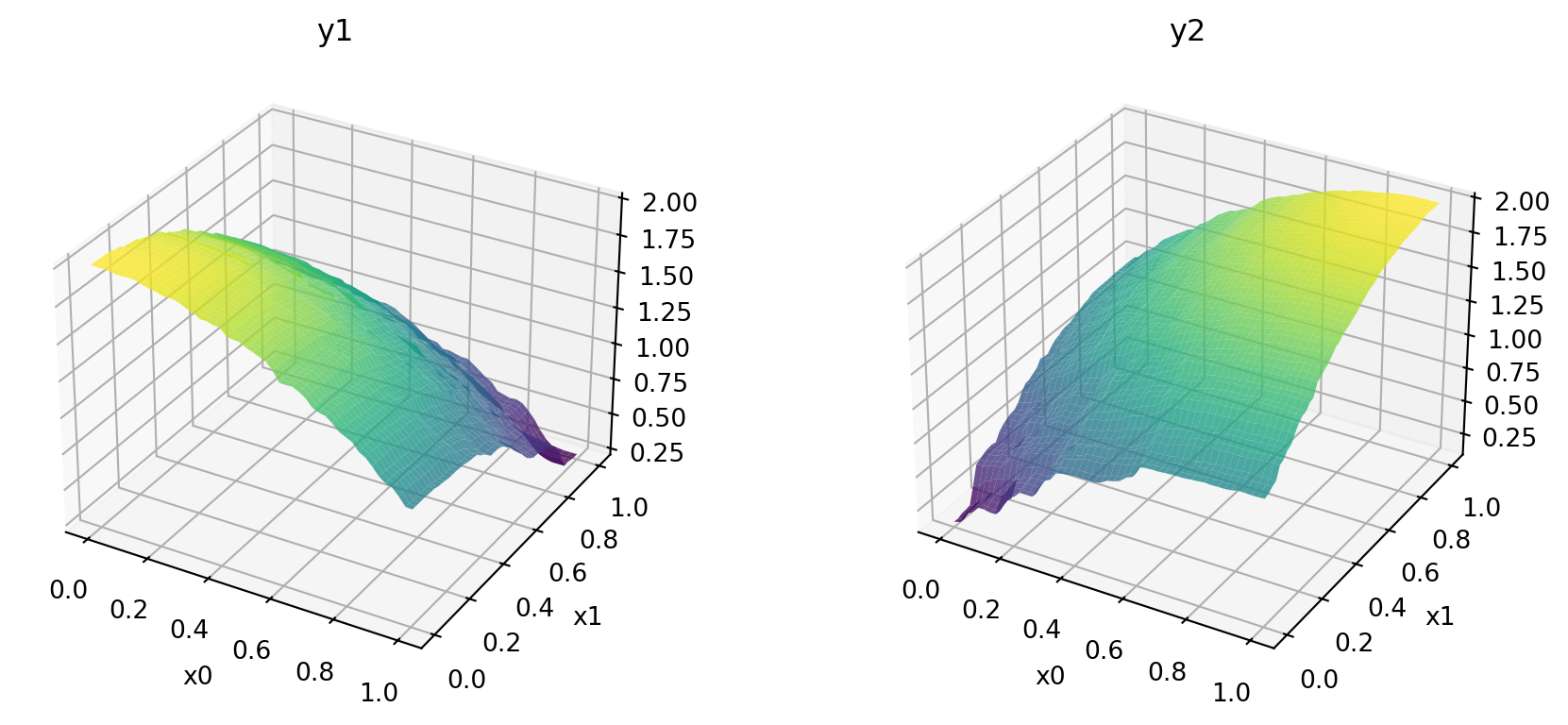

Generate X_base in the range [0,1] as input data and evaluate the two-objective maximization function mo_conv2_max.

A smooth, convex two-objective maximization problem on [0, 1]^2 using flipped versions of the minimization objectives:

\[\begin{align} f1(x, y) = 2 - (x^2 + y^2)\\ f2(x, y) = 2 - ((1 - x)^2 + (1 - y)^2) \end{align}\]

It has the following properties:

- Domain: \([0, 1]^2\)

- Objectives: maximize both \(f1\) and \(f2\)

- Ideal points: \((0, 0)\) for \(f1\) (gives \(f1=2\)); \((1, 1)\) for \(f2\) (gives \(f2=2\))

- Pareto set: line \(x = y\) in \([0, 1]\)

- Pareto front: convex quadratic trade-off \(f1 = 2 - 2t^2\), \(f2 = 2 - 2(1 - t)^2\), \(t \in [0, 1]\)

X_base = np.random.rand(500, 2)

y = mo_conv2_max(X_base)The RandomForestRegressor models are fitted for each objective.

models = []

for i in range(y.shape[1]):

model = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=n_estimators, random_state=random_state, max_depth=max_depth)

model.fit(X_base, y[:, i])

models.append(model)# calculate base Morris-Mitchell stats

phi_base, J_base, d_base = mmphi_intensive(X_base, q=2, p=2)

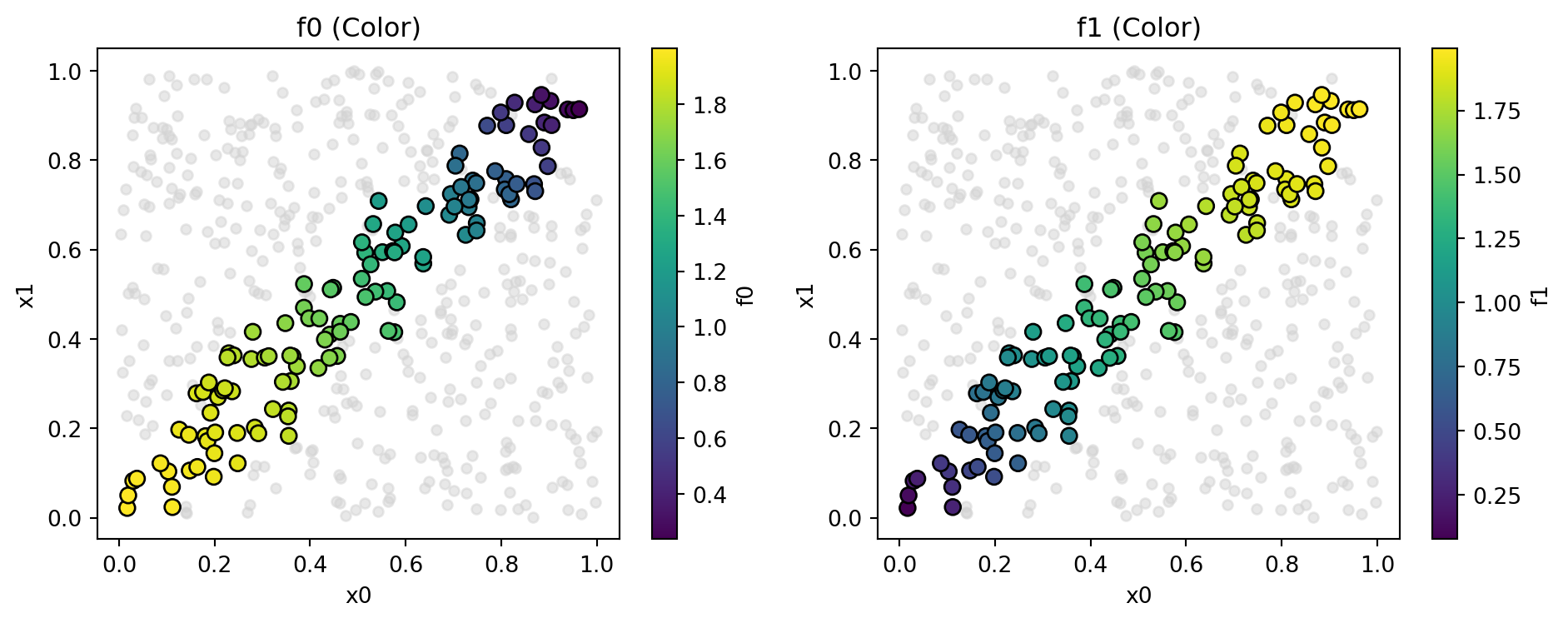

print(f"phi_base: {phi_base}, J_base: {J_base}, d_base: {d_base}")phi_base: 6.212013258255464, J_base: [1 1 1 ... 1 1 1], d_base: [0.00133909 0.00224301 0.00243956 ... 1.32508419 1.3359148 1.338386 ]Figure 24.10 shows the surfaces of the two objectives using the fitted models.

x_min = 0

x_max = 1

combinations = [(0,1)]

target_names = ["y1", "y2"]

mo_xy_surface(models, bounds=[(x_min, x_max), (x_min, x_max)], target_names=target_names)

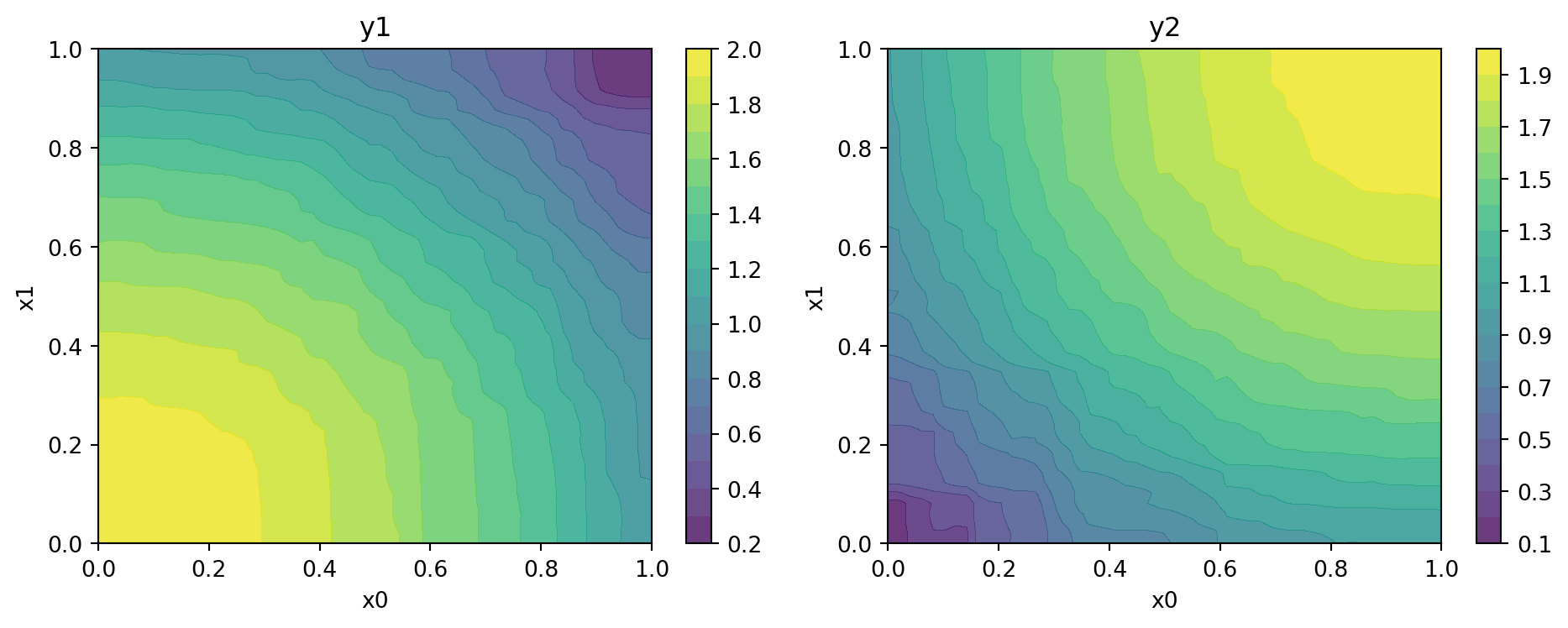

Figure 24.11 shows the contours of the two objectives using the fitted models.

x_min = 0

x_max = 1

mo_xy_contour(models, bounds=[(x_min, x_max), (x_min, x_max)], target_names=target_names)

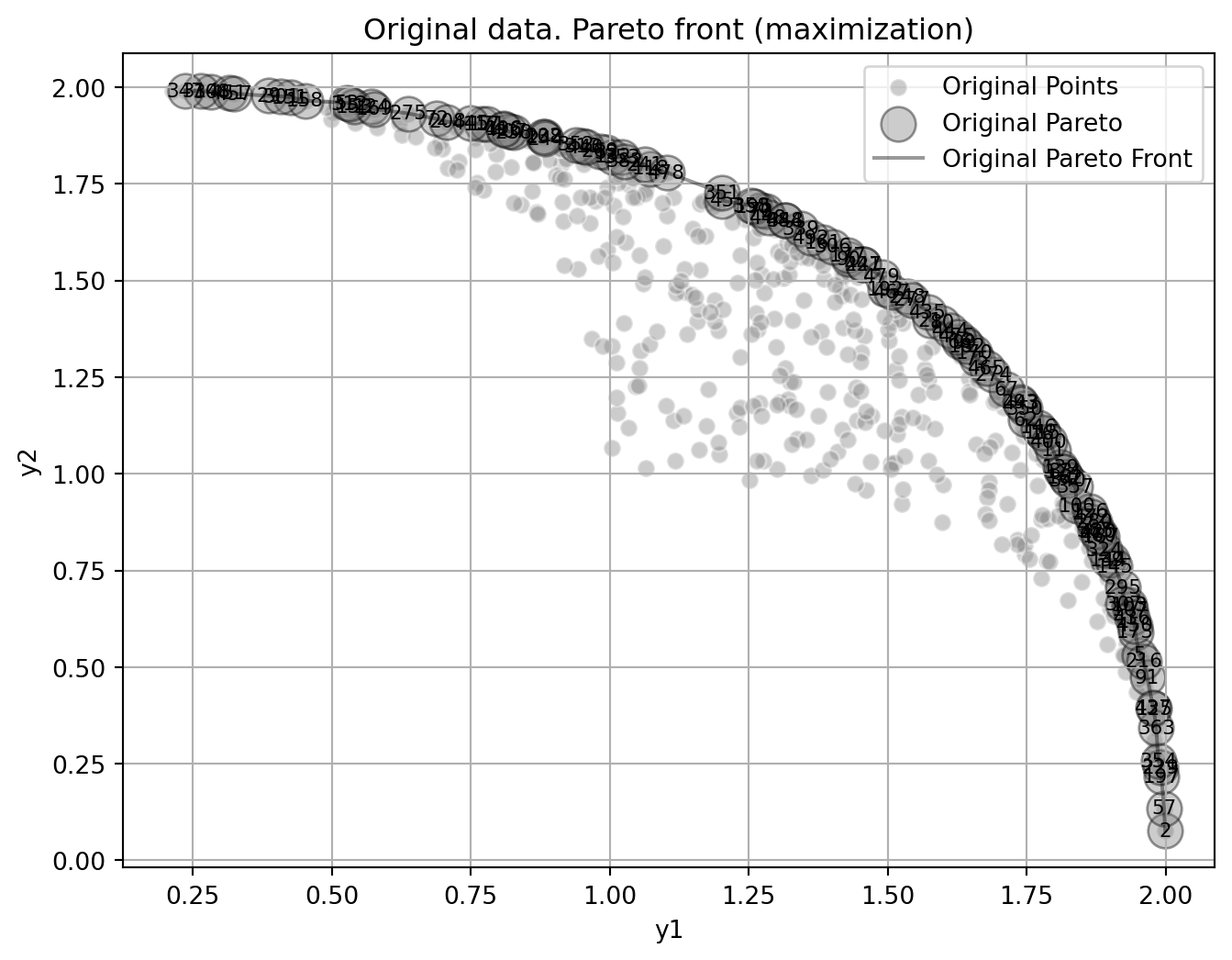

Figure 24.12 shows the Pareto front of the original data.

plot_mo(y_orig=y, target_names=target_names, combinations=combinations, pareto="max", pareto_front_orig=True, title="Original data. Pareto front (maximization)", pareto_label=True)

Figure 24.13 visualizes the Pareto-optimal points, i.e., the points in the input space that correspond to the Pareto front:

mo_pareto_optx_plot(X=X_base, Y=y, minimize=False)

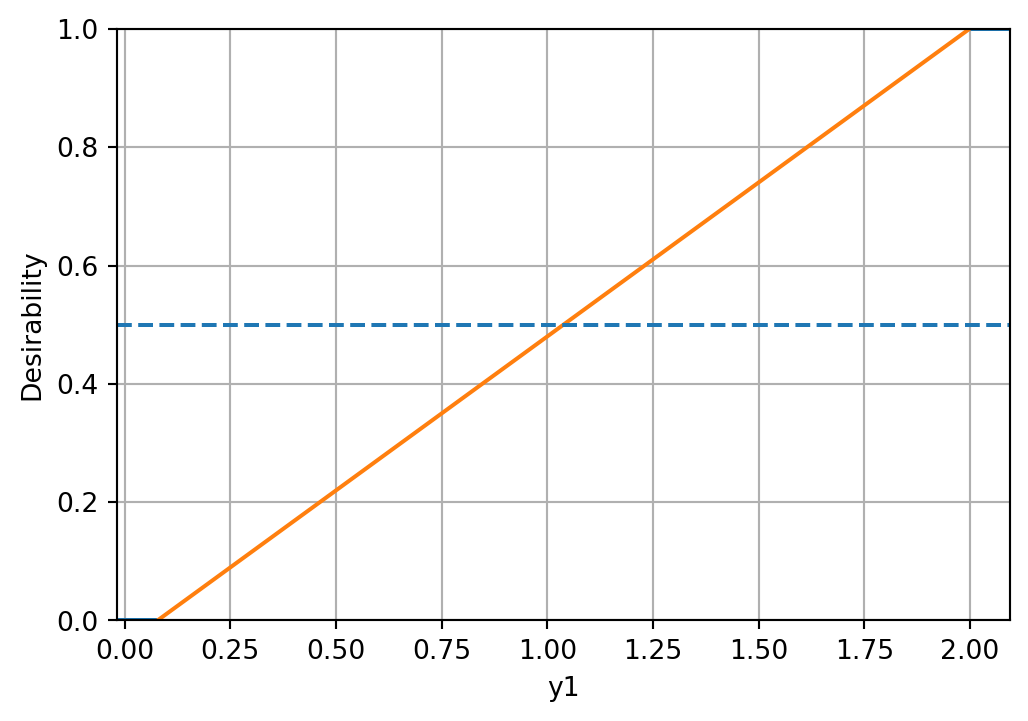

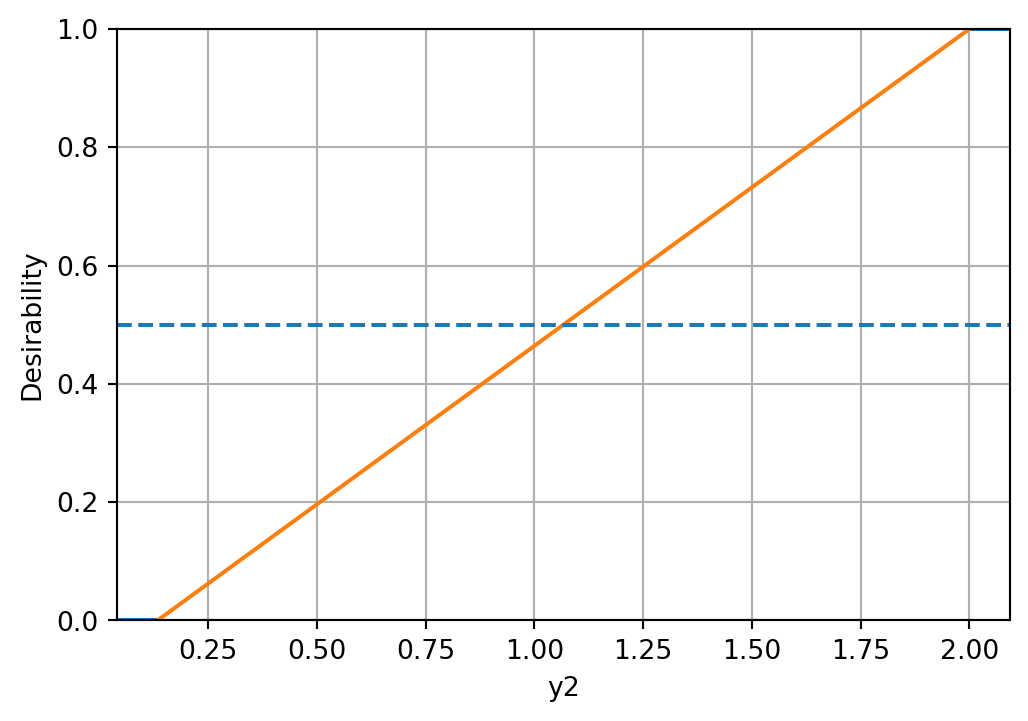

Compute desirability functions for each objective:

d_funcs = []

for i in range(y.shape[1]):

d_func = DMax(low=np.min(y[:, i]), high=np.max(y[:, i]))

d_funcs.append(d_func)The desirability functions can be visualized as follows:

d_funcs[0].plot(xlabel=target_names[0], figsize=(6,4))

d_funcs[1].plot(xlabel=target_names[1], figsize=(6,4))

The minimal expected improvement of the Morris-Mitchell criterion is defined as 1 percent of the base value, and the maximal expected improvement as 10 percent of the base value. Then, the desirability function for Morris-Mitchell objective can be defined as follows:

# imp_min = phi_base * 0.01

# imp_max = phi_base * 0.1

# d_mm = DMax(low=imp_min, high=imp_max)

# d_mm.plot()Combine into overall desirability

# D_overall = DOverall(*d_funcs, d_mm)

D_overall = DOverall(*d_funcs)Now we can call the mo_mm_desirability_function with a test point:

x_test = np.array([0.5, 0.5]) # Example test point

neg_D, objectives = mo_mm_desirability_function(x_test, models, X_base, J_base, d_base, phi_base, D_overall, mm_objective=False)

print(f"Negative Desirability: {neg_D}")

print(f"Objectives: {objectives}")Negative Desirability: -0.7374994411771443

Objectives: [np.float64(1.4906734308429819), np.float64(1.5123762382740051)]mo_xy_desirability_plot(models, bounds=[(x_min, x_max), (x_min, x_max)], X_base=X_base, J_base=J_base, d_base=d_base, phi_base=phi_base, D_overall=D_overall, mm_objective=False)

24.9 Jupyter Notebook

- The Jupyter-Notebook of this chapter is available on GitHub in the Sequential Parameter Optimization Cookbook Repository