import numpy as np

from spotoptim.surrogate import Kriging

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# 1D example for visualization

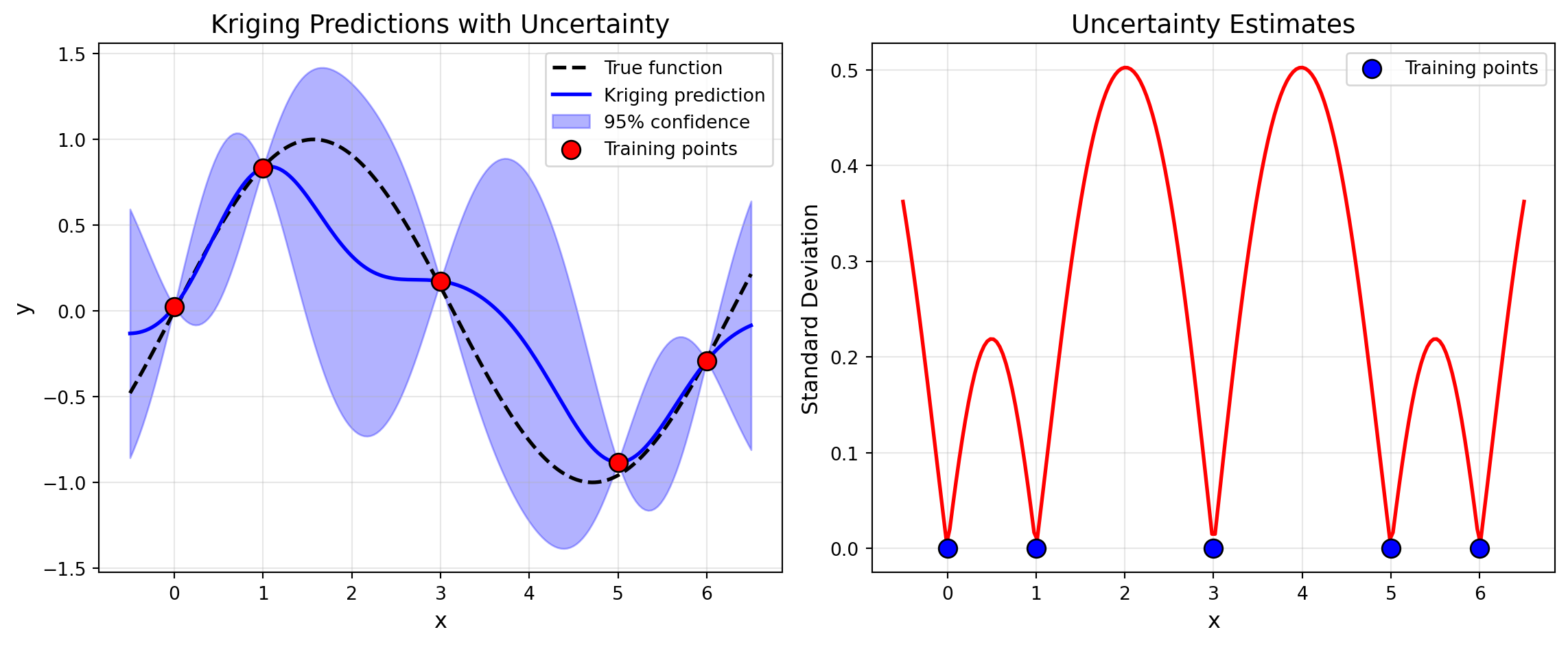

np.random.seed(42)

X_train = np.array([[0.0], [1.0], [3.0], [5.0], [6.0]])

y_train = np.sin(X_train.ravel()) + 0.05 * np.random.randn(5)

# Fit Kriging model

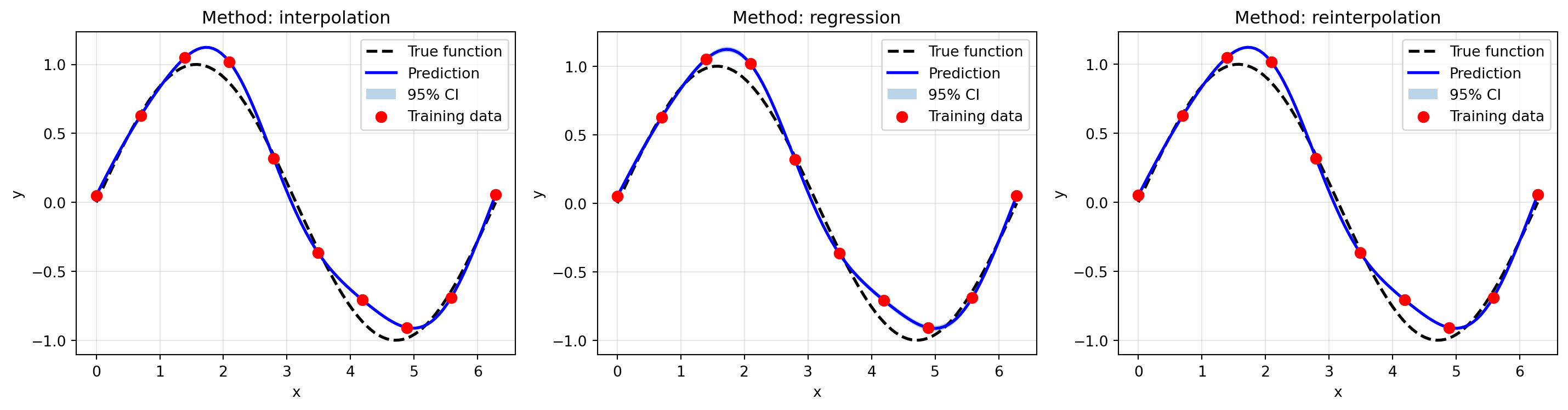

model = Kriging(method='regression', seed=42, model_fun_evals=50)

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Dense test points

X_test = np.linspace(-0.5, 6.5, 200).reshape(-1, 1)

y_pred, y_std = model.predict(X_test, return_std=True)

# True function

y_true = np.sin(X_test.ravel())

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.plot(X_test, y_true, 'k--', label='True function', linewidth=2)

plt.plot(X_test, y_pred, 'b-', label='Kriging prediction', linewidth=2)

plt.fill_between(X_test.ravel(),

y_pred - 2*y_std,

y_pred + 2*y_std,

alpha=0.3, color='blue', label='95% confidence')

plt.scatter(X_train, y_train, c='red', s=100, zorder=5,

edgecolors='black', label='Training points')

plt.xlabel('x', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('y', fontsize=12)

plt.title('Kriging Predictions with Uncertainty', fontsize=14)

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.plot(X_test, y_std, 'r-', linewidth=2)

plt.scatter(X_train, np.zeros_like(X_train), c='blue', s=100,

zorder=5, edgecolors='black', label='Training points')

plt.xlabel('x', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('Standard Deviation', fontsize=12)

plt.title('Uncertainty Estimates', fontsize=14)

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("Key observations:")

print("- Uncertainty is low near training points")

print("- Uncertainty is high far from training data")

print("- This guides acquisition functions (e.g., EI exploits low uncertainty)")